Lightweight Coordination on Azure App Service

Problem

Before diving into implementation details, it’s important to understand the context of the problem. In this case, we had logic similar to the following pseudocode:

...

var data = ReadSharedData();

var newData = ModifyData(data);

WriteSharedData(newData);

...Some readers no doubt recognize this pattern and can suggest several common approaches to ensure proper execution on a single machine (i.e., thread-based concurrency controls such as lock/monitor). However, we would still have a problem when this logic executes on multiple machines at the same time.

NOTE: While it is possible to rewrite the logic to remove the need for centralized coordination, in some cases rewriting existing logic may not be possible.

Typically in these scenarios, we could employ services such as Redis or ZooKeeper to provide such locking, or even leverage Azure Blob storage leases (see https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/architecture/patterns/leader-election). While these are indeed adequate solutions, they require the deployment of additional services, as well as potentially administering highly-available deployments (specifically for Redis and ZooKeeper). For some teams that may not have these skills and/or have access to deploy such resources, this can present an enormous challenge. Therefore, for this specific use case we will be showing how to provide similar control within the application itself without the need for any additional services in order to avoid these problems.

Some App Service Internals

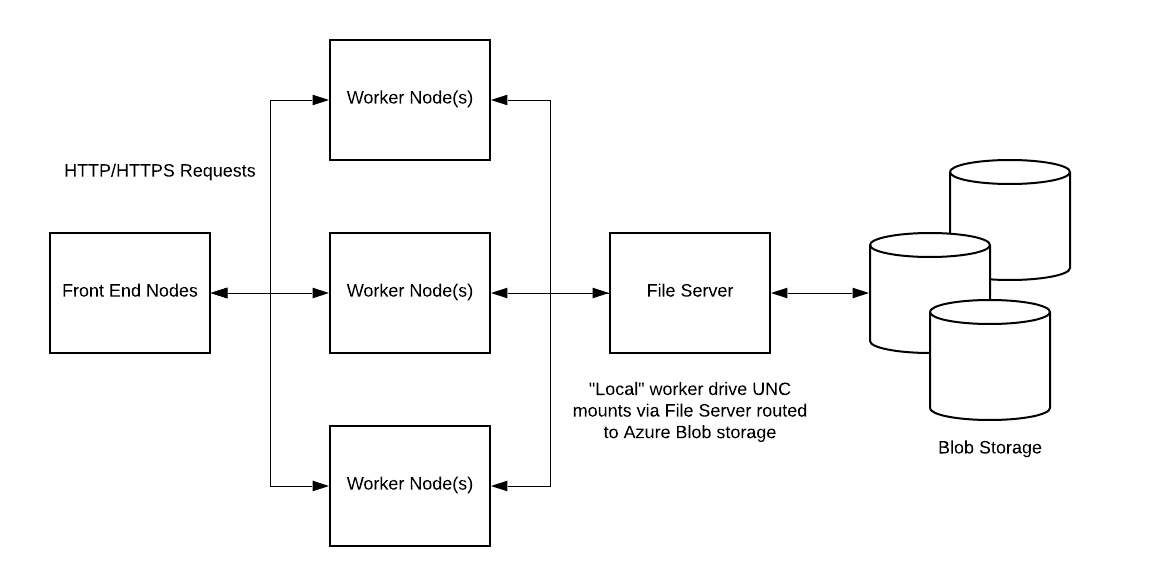

Azure App Service is a service for hosting web applications, REST APIs, and mobile back ends without worrying about managing infrastructure (additional details here). Additionally, you can specify options for scaling-out (via multiple instances), effectively running many instances of your application across a pool of machines while letting the Azure platform handling deployment of your code and data to these instances. In order to ensure this, one of the techniques used is to mount an underlying file share that contains your code and/or data as shown below:

For more details, see the following articles on App Service UNC Shares and Understanding the Azure App Service file system. It will be this file share that gives us a common location that every worker node in the deployment is able to read and write to - we’ll be taking advantage of that to implement our example solution.

Approach

The problem of ensuring proper execution across more than a single machine is the focus of distributed coordination, handled by either optimistic or pessimistic methods. In this case, we’ll be implementing distributed locking, a form of pessimistic concurrency control where each individual request execution acquires and exclusive lock on a shared resource before proceeding. Other executions must wait, effectively giving a serial execution (or “one at a time” semantics), even across multiple concurrent executions. Note, however, that pessimistic locking does have significant performance overhead compared to optimistic techniques - this needs considered carefully before adopting such approaches.

Using our previous example pseudocode above, our solution would now look something like this if we guard it with our lock constructs:

...

AcquireLock();

var data = ReadSharedData();

var newData = ModifyData(data);

WriteSharedData(newData);

ReleaseLock();

...Combining this with the knowledge of the underlying UNC share, we can simulate the distributed lock concept by opening files on the file share with exclusive “write” access (thereby providing our synchronization point). Other clients/machines that attempt to acquire the same lock will be blocked until others release it. Time for some code!

Implementation

For this sample, I’m using NodeJS (specifically the proper-lockfile NPM package - details here) which gives a nice interface over locking and unlocking files. It also ensures that measures are taken to avoid reading/writing from the local file system cache (including writing folders, which are always sync’d) and opening files in modes that instruct the OS to not use the local cache.

Basic pattern for using this approach is shown below (example in TypeScript):

import * as lockfile from "proper-lockfile";

// Other app code...

await lockfile.lock(“somefile.lock”, {retries: 5});

// TODO: Do work here

await lockfile.unlock(“somefile.lock”);

// Resume app code...To test this approach, I’ve put together a small NodeJS sample that uses this pattern to increment a counter across all machines (I’ve included a few sample load testing scripts in the repo). I’m also running 3 instances of my application (running a Basic "B1" sku) to ensure multiple machines are in play. If successful, the counter should monotonically increase, up to the the number of tests we run.

The sample application has a very simple REST API that can be trigger from using curl or any other tool:

- POST /incrementSafe : safely increments the shared counter.

- POST /incrementUnsafe : increments the shared counter without leveraging the safety lock.

We'll use both of these methods to test the impact of the locking solution in the next section.

Testing

In our first test, we’ll run a single script, which effectively has no parallelism. In this case, we fully expect the counter to read 100:

New counter value is: 1 New counter value is: 2 New counter value is: 3 New counter value is: 4 ... New counter value is: 97 New counter value is: 98 New counter value is: 99 New counter value is: 100

In the next test, we’ll run 2 scripts in parallel - assuming all requests complete, the counter should now read 2 x 100 = 200:

New counter value is: 1 New counter value is: 2 New counter value is: 3 New counter value is: 4 ... New counter value is: 197 New counter value is: 198 New counter value is: 199 New counter value is: 200

Finally, let’s test 4 scripts, which should give us 4 x 100 = 400:

New counter value is: 1 New counter value is: 2 New counter value is: 3 New counter value is: 4 ... New counter value is: 397 New counter value is: 398 New counter value is: 399 New counter value is: 400

Looks like we’ve achieved our goal - parallel requests correctly modifying (incrementing) a shared value (in this case, a simple counter). However, let’s also look at the “negative” result - that is, if we test this last example without the synchronization code, we should see lost writes and/or corrupted data:

New counter value is: 1

New counter value is: 1

New counter value is: 2

New counter value is: 3

New counter value is: 3

New counter value is: 3

New counter value is: 3

New counter value is: 4

...

New counter value is: 297

New counter value is: 297

New counter value is: 297

ERROR: {}

New counter value is: 299

ERROR: {}

...

New counter value is: 326

New counter value is: 326

New counter value is: 328

New counter value is: 327

New counter value is: 327

New counter value is: 327

New counter value is: 327

Note that we now have lost writes caused by the last-write-wins behavior of unsynchronized code - exactly what we expected to see with contention on a shared resource. Also, the ERROR: {} blocks indicate there was corruption of the file during reading, caused by concurrent overwriting of the counter file. These errors demonstrate how problems can appear out of nowhere when deploying to environments that break core assumptions of the underlying code (in this case, singular execution).

Limitations

As with any approach, one size does not fit all, and this won’t work for every scenario. Most notably, high throughput scenarios are likely to suffer using this approach, as we need to consider the limitations on the underlying file share and the constant additional network communication that is occurring to keep the file share synchronized. That said, this may be a useful approach for low- to medium- throughput scenarios which have logic that isn’t easily adopted to such distributed environments. Also, note that extra care needs to be taken to ensure proper handling of error conditions - crashing in a "locked" state may leave your application unavailable until the exclusive file lock is released (likely a less than ideal situation for your end users).

Cheers!!!