Virtual Network Verification using SMT Solvers

Background

When verifying network infrastructure configuration and behavior, approaches typically fall within the following approaches:

-

Configuration Verification

Example: Is the device configured the way is should be?

-

Explicit flow testing (positive cases)

Example: Can a packet flow from point A to point B?

-

Explicit flow testing (negative cases)

Example: Are packets blocked from flowing from point B to point C?

-

Exploratory testing

Example: Find all addresses/ports that violate a business rule

Each of these approaches has their own advantages and challenges. Following the outline above, we can enumerate these tradeoffs:

-

Configuration Verification

Advantages: Relatively easy to check; Doesn’t require software installation / etc.; simply "reflect" configuration and compare to a known-good.

Disadvantages: Only checks that configuration is present; doesn’t verify behavior.

-

Explicit flow testing (positive cases)

Advantages: Exact answers that match behavioral specifications (e.g., VM-A can talk to VM-B). Requies testing from each node and/or installing agents.

Disadvantages: May require installation of testing utilities and or direct access (compromising validation/etc in secure environments).

-

Explicit flow testing (negative cases)

Advantages: Concrete answers that match behavioral specifications (e.g., VM-B cannot talk to VM-C). Requies testing from each node and/or installing agents.

Disadvantages: Typically harder to derive; can take longer to maintain and update. May require installation of testing utilities and/or direct access (compromising validation/etc)

-

Exploratory testing

Advantages: Uncovers unintended/unknown communication paths that can potentially lead to security issues.

Disadvantages: Can be computationally very expensive (enumerating IP's x Ports x nodes); May require installation of testing utilities; May falsely trigger IDS/etc. systems

While the first 3 options have relatively known solutions, the goal here is to explore reducing the computational complexity of the last option ("Exploratory testing") to provide more rapid validation that no unknown beahviors are present.

To help reduce this complexity, we are going to examine leveraging the Z3 SMT solver from Microsoft Research (along with the open source Zen library) to help evaluate a given set of rules and determine if they adhere to a set of stated business requirements. We can then search for conditions that violate these constraints that may not be obvious (especially in complex/nested rulesets).

What are Z3 and Zen?

Z3 was developed in the Research in Software Engineering (RiSE) group at Microsoft Research and is targeted at solving problems that arise in software verification and software analysis. Source code and more in-depth documentation for Z3 can be found here: https://github.com/Z3Prover/z3.

Zen is a research library and verification toolbox that allows for creating models of functionality. The Zen library has a number of built-in tools for processing these models, including a compiler, model checker, and test input generator (from https://github.com/microsoft/zen).

But why use a solver in the first place? There are many cases where brute-force evaluation of a solution is not computationally feasible. For example, let’s consider a (basic) model of a possible ACL rule. This rule contains the following properties:

- Source IP address

- Destination IP address

- Source port

- Destination port

- Action (allow / deny)

If we only consider IPv4 address where each IP address is represented as a 32-bit number and each port is a 16-bit number, the solution space for this problem is enormous: 232 × 232 × 216 × 216 = 296 unique configurations (that’s 79,228,162,514,264,337,593,543,950,336 in numerical form). Simply crawling all possible combinations of ip addresses and ports would take over 2 trillion years even while processing at a rate of 1 billion combinations per second - definitely not a feasible approach. Instead, we can formulate this problem as a first-order logic problem, and let a solver search the problem space given the correct constraints in much shorter time - usually in only a few seconds.

Formulating the Problem

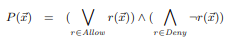

The first step is to state the desired network properties (e.g, invariants) as boolean function expressions. For example, when evaluating ACL rules in a "deny overrides all" type approach, the following type of expression could be used:

In this expression, P(x) represents an overall policy resule, with r(x) denoting a single rule within that policy.

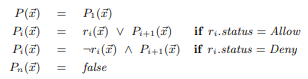

Alternatively, we could also evaluate against a "first matches" type approch, in which we would have an approach like this following:

In this expression, we are looking at each rule and checking to see if it a packet matches the rule. If none match, we assume the packet is blocked by the policy.

NOTE: The above equations are from the SecGuru paper found in the references noted in the GitHub repo.

Worked Example: Z3

We'll start by looking at an example of how to encode these invariants in the Z3 dialect (specifically, the SMTLIB 2.0 format). To begin with, we'll use a basic set of ACL rules (simplified here for demonstration). Our VNET in this example is 10.0.1.0, and ACL is defined as:

- Src = VNET, Dest = VNET, Src Port = any, Dest Port = any => Allow

- Src = VNET, Dest = 0.0.0.0/0, Src Port = any, Dest Port = 80 => Allow

- Src = VNET, Dest = 0.0.0.0/0, Src Port = any, Dest Port = 443 => Allow

- Src = 0.0.0.0/0, Dest = VNET, Src Port = any, Dest Port = 8080 => Allow

- Deny all others

The first step we need to do is correctly model our ACL rules, and to do that we need to first convert IP addresses into something that Z3 understands. Since we’re dealing primarily with IPv4 in this example, 32-bit integers are a natural choice (and the conversion from IPv4 to uint32 is straightforward). Ports numbers (while already integers) should technically be 16-bit unsigned integers (limiting the range from 0 to 65535); for this example we’ll simply add additional variants to ensure they fall within the uint16 range.

So, In our example rule set above we would have the following once converted to numerical form:

- VNET start address 10.0.1.0 = 167772416

- VNET end address 10.0.1.255 = 167772671

- Internet (0.0.0.0/0) is all other Int32 numbers, excluding the private ranges.

Note, for this document we’ll keep is simple and assume we can use all other addresses starting at 1.0.0.1 (or 16777217) and ending at 223.255.255.255 (or 3758096383).

Next we need to build our “matching” function so we can teach Z3 how to evaluate an ACL (note in this prototype we’re skipping priority values and using a “first match” approach):

(define-fun TestPacket () Bool

(ite (= TestAccept true) true TestDeny)

)Here, we are checking for accepted values first, then falling through to the deny rule set if nothing is found (note the “ite” function in Z3 is “if then else”). Each of the “TestAccept” and “TestDeny” methods is composed of a list or rules as shown below:

; Tests the "accept" and “deny” criteria

(define-fun TestAccept () Bool

(or

; Rule 1

; Rule 2 / etc.

)

)

(define-fun TestDeny () Bool

(not (or

; Rules

))

)Now that we have a basic evaluation function, we need to encode our rules. Again, we note the packet is allowed if and only-if all parameters match (source IP/port and destination IP/port in this example) - meaning we can encode the evaluation function as follows:

; Define the basic ACL matching behavior

(define-fun matches (

(srcIpLower Int) (srcIpUpper Int)

(dstIpLower Int) (dstIpUpper Int)

(srcPortLower Int) (srcPortUpper Int)

(dstPortLower Int) (dstPortUpper Int)

) Bool

(and

(<= srcIpLower src)

(<= src srcIpUpper)

(<= dstIpLower dst)

(<= dst dstIpUpper)

(<= srcPortLower srcPort)

(<= srcPort srcPortUpper)

(<= dstPortLower dstPort)

(<= dstPort dstPortUpper)

)

)Finally, we can encode our rules to call this method using the ACL description from above. These rules will be of the following form:

Here, we are invoking the “matches” function with the 8 specified parameters; in this example, we have the source IP range (first 2 params) equal to the VNET range (as integers). The destination is the same, as we are allowing packets within the VNET to flow. Finally, the source and destination port ranges cover the entire port range, effectively meaning “any” port. This reflects our first ACL “Accept” rules of “Allow VNET to VNET communication”.

Once all the remaining rules are in place, we need to finally assert that our business rules are not violated. In this case, we are looking for cases where inbound internet traffic is mistakenly allowed. These packets share the following characteristics:

- The packet is allowed in (via “matches” function returning “true”)

- Source is anywhere on the Internet

- Destination is anywhere in the VNET

- Any source / destination port number

These assertions are then added to our Z3 formulation as follows:

; We want cases where a packet is accepted

(assert TestPacket)

; ...where destination is the VNET

(assert (and (>= dst 167772416) (<= dst 167772671)))

; ...and source is internet

(assert

(and

(not (and (>= src 167772416) (<= src 167772671)))

(and (>= src 16777217) (<= src 3758096383))

)

)

;constrains ports to normal range

(assert (and (>= srcPort 0) (<= srcPort 65535)))

(assert (and (>= dstPort 0) (<= dstPort 65535)))Once added, we can run our program and let Z3 attempt to solve for all cases where these invariants are satisfied. Note that Z3 can return with “sat” (satisfiable) or “unsat” (unsatisfiable); the latter meaning no solution is found (which is what we hope to find in this case).

Running the model formulation above gives:

unsat

Z3(75, 10): ERROR: model is not availableThis means that no solution is found, and we do not have any “holes” in our ACL policies (as defined in this simulation) - which in this case is a successful result.

We should also verify that if we now allow inbound connectivity, we should get a “sat” model result. So first lets add 2 constraints to allow inbound packets headed to port 8080:

; Inbound internet traffic from internet is allowed on port 8080

(matches 16777217 167772415 167772416 167772671 0 65535 8080 8080)

(matches 167772672 3758096383 167772416 167772671 0 65535 8080 8080)

After adding these rules to the “TestAccept” matching function, we can re-run the model:

sat

(model

(define-fun dst () Int

167772416)

(define-fun src () Int

16777217)

(define-fun srcPort () Int

0)

(define-fun dstPort () Int

8080)

)The solver has correctly found that inbound communications from the internet (in this case from 16777217, which is 1.0.0.1) is allowed to the VNET address 167772416 (which is 10.0.1.0). Note that when a model is satisfiable, the model supporting that theory can be returned.

Making Things More "Zen"

While the Z3 SMTLIB format is exact, it can be very tedious and difficult to understand, especially for those who have never worked with a LISP-like format. Enter the Zen library.

Zen will allow us to use familiar programming conventions to simplify how we express our models, and even let us use different solvers (even though this case will be using the Z3 solver). Let's take a look at how we could encode are assertions above using Zen from C# (.NET Core):

inboundAllowed.Invariant = (packet, result) =>

{

Zen srcIp = packet.GetSrcIp();

return And(

Or( // Looking for packets _not_ coming from the VNET ..

And(

srcIp >= IPAddressUtilities.StringToUint("1.0.0.1"),

srcIp < IPAddressUtilities.StringToUint("10.0.1.0")

),

And(

srcIp > IPAddressUtilities.StringToUint("10.0.1.255"),

srcIp <= IPAddressUtilities.StringToUint("223.255.255.255")

)

),

result == true // ..that are allowed by ACL policy

);

}; This is much more concise and familiar, and allows us to encode more complicated rulesets (such as "First Match") using language conventions that are likely already in use.

For a complete, worked example of the "First Match" strategy, have a look at this GitHub Repo I put together to test various assertions against VNETs. Note this sample mainly works off an example / demo dataset - however there is a pluggable IRulesetLoader interface that can be swapped out to read from other formats or even pull from Azure / AWS / GCP / etc. (I've started a basic Azure implementation and will merge in later).

Prior Work

There are many applications of SMT solvers for configuration verification, including on the Azure platform itself as well as AWS. Additionally, much of this work has been influenced by some excellent existing efforts, listed below. These publications definitely provided the impetus for putting this content together:

- "SecGuru: Automated Analysis and Debugging of Network Connectivity Policies", https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/secguru.pdf

- "Automated Analysis and Debugging of Network Connectivity Policies", https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/secguru.pdf

- "Checking Cloud Contracts in Microsoft Azure", https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/nbjorner-icdcit2015.pdf

- "Checking Firewall Equivalence with Z3", https://ahelwer.ca/post/2018-02-13-z3-firewall/

Future Work

While this is only a quick explanation and demonstration, the code in the repo is lacking several features which could be used to properly validate existing network infrastructure. These are (in no particular order):

- Building a correct graph of network connected device in order to property combine and order ACL's

- Handling network address translation that may give false results due to packets matching/not-matching.

- Additional parser (IRulesetLoader) implementations to digest existing network configurations.

- Testing build out

Feedback and/or comments welcome...would love to hear if any of you have used similar formal analysis tools to help validate complex infrastructure deployments. Cheers!